In the world of film, the art of storytelling is not just about the script, the actors, or the director’s vision. It’s also about the subtle craft of film editing. The editor’s work often goes unnoticed by the average viewer, yet it is their careful selection and arrangement of shots that ultimately shapes the narrative, rhythm, and pace of the film. One approach that has gained prominence over the years is minimalism in film editing. This technique, often encapsulated by the phrase “less is more,” seeks to tell a story in the most efficient and impactful way possible, without unnecessary embellishments or distractions. This article will delve into the role of minimalism in film editing and its profound impact on storytelling.

Understanding Minimalism in Film Editing

Minimalism in film editing is a philosophy and technique that focuses on simplicity and precision. It’s about making every cut, every transition, and every shot purposeful and meaningful. The role of a film editor in minimalist editing is akin to that of a sculptor, carefully chiseling away unnecessary elements to reveal the essence of the narrative.

The evolution of minimalist editing techniques can be traced back to the early days of cinema. Filmmakers like Yasujirō Ozu, Robert Bresson, and later, Andrei Tarkovsky, were known for their minimalist approach. They often used long takes and avoided unnecessary cuts or transitions, allowing the story to unfold naturally and the audience to immerse themselves in the film’s world.

In contemporary cinema, directors like Sofia Coppola, Wes Anderson, and the Coen Brothers have embraced minimalism in their editing styles. Their films often feature long, uninterrupted shots and a restrained use of cuts, creating a unique rhythm and pacing that sets them apart.

Understanding minimalism in film editing is not just about recognizing these techniques, but also appreciating the purpose behind them. Minimalist editing is not about being sparse for the sake of it; it’s about enhancing the storytelling process, creating a deeper connection between the audience and the narrative. It’s about knowing when to cut and when to let a shot linger, understanding that sometimes, silence can speak louder than words, and that less can indeed be more.

The Power of Less: Techniques in Minimalist Film Editing

Minimalist film editing is not about a lack of editing, but rather a more intentional and thoughtful approach to the process. It’s about choosing the most effective way to tell the story, even if that means using fewer cuts or transitions. Here are some of the key techniques used in minimalist film editing:

- Continuity Editing: This is the most common form of editing, designed to maintain a continuous and clear narrative. In minimalist editing, continuity editing is used sparingly and intentionally, ensuring that each cut contributes to the story and the emotional impact of the scene.

- Cross Cutting: This technique involves cutting between two or more different scenes that are happening simultaneously. Minimalist editors use cross-cutting to create tension and contrast, often with fewer cuts to maintain a slower pace and allow the audience to fully absorb each scene.

- Cutaway: A cutaway involves cutting from the main action to a different scene or detail, then back to the original scene. In minimalist editing, cutaways are used sparingly and are often focused on significant details that enhance the narrative or character development.

- Dissolve: A dissolve is a transition between two shots, where the first shot gradually fades out while the second shot gradually fades in. Minimalist film editing often uses dissolves to signify the passage of time or a change in location, creating a smooth and seamless transition between scenes.

- Fade: Fades, whether to black, white, or another color, are often used in minimalist editing to signify the end of a scene or a significant shift in the narrative. The simplicity of a fade transition aligns well with the minimalist approach.

- J & L Cut: These cuts are named for the shape they make on an editing timeline. A J-cut is when the sound from the next scene starts before the visual, and an L-cut is when the visual from the next scene starts before the sound. These cuts are used in minimalist editing to create a smooth and natural transition between scenes.

- Jump Cut: A jump cut is a cut between two shots of the same subject, with a slight change in angle or composition. In minimalist editing, jump cuts are used sparingly and intentionally, often to show a passage of time or a sudden change in the narrative.

- Match Cut: A match cut involves cutting from one shot to another where the two shots are matched by the action or subject. In minimalist editing, match cuts are used to create visual continuity and narrative cohesion.

- Montage: A montage is a sequence of shots edited together to condense space, time, and information. In minimalist editing, montages are often simple and focused, avoiding unnecessary embellishment.

- Shot/Reverse Shot: This is a common editing technique where one character is shown looking at another character, and then the other character is shown looking back. In minimalist editing, shot/reverse shot is used to focus on the characters’ reactions and emotions, often with fewer cuts to maintain a slower pace.

Each of these techniques, when used effectively, can contribute to the minimalist storytelling process, enhancing the narrative and emotional impact of the film. The power of minimalism in film editing lies in the understanding that sometimes, less truly is more.

Case Studies: Minimalism in Action

To truly understand the impact of minimalism in film editing, it’s insightful to examine specific films that have effectively utilized this approach. Here are a few examples:

No Country for Old Men – This film, directed by the Coen Brothers, serves as a masterclass in minimalist editing. The narrative unfolds through scenes that often play out in long, uninterrupted takes, creating a slow-burning tension that’s palpable. The Coen Brothers’ restrained use of cuts allows the audience to fully immerse themselves in the story and the stark landscape of West Texas.

Lost in Translation – Sofia Coppola’s film uses minimalist editing to mirror the feelings of isolation and disconnection experienced by its characters in a foreign city. The film features long takes and a slow pace, allowing the audience to experience the same sense of time and space as the characters. The sparse editing also emphasizes the emotional depth of the characters and their evolving relationship.

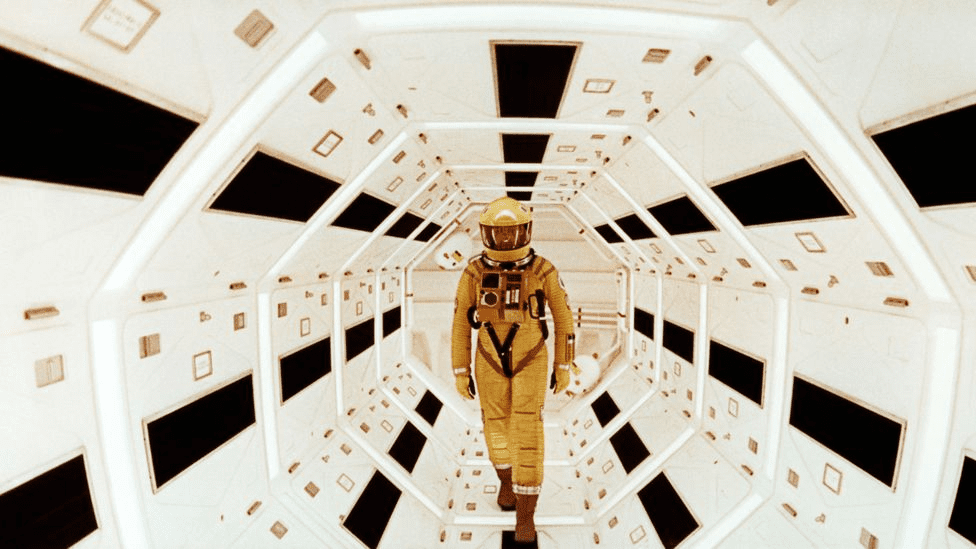

2001: A Space Odyssey – Stanley Kubrick’s epic science fiction film is renowned for its minimalist editing. The film is filled with long, lingering shots that create a sense of vastness and isolation in space. Kubrick’s use of match cuts, most notably the transition from the bone thrown by the ape to the spaceship in orbit, is a powerful example of minimalist editing enhancing the narrative.

The Impact of Minimalist Editing on the Audience

Minimalist editing has a profound impact on how audiences perceive and engage with a film. By reducing distractions and focusing on the essential elements of the story, minimalist editing allows the audience to immerse themselves fully in the narrative.

The use of long takes and fewer cuts can create a more contemplative and introspective viewing experience. It encourages the audience to pay closer attention to the details on screen, from the actors’ performances to the cinematography. This can lead to a deeper emotional connection with the characters and a greater appreciation of the film’s thematic depth.

Moreover, minimalist editing can influence the pacing and rhythm of the film. A slower pace can create a sense of tension, anticipation, or introspection, depending on the context. This can enhance the emotional impact of the film and leave a lasting impression on the audience.

The psychological impact of minimalist editing should not be underestimated. By stripping away unnecessary elements, minimalist editing can create a more intimate and visceral viewing experience. It can challenge the audience to engage more actively with the film, sparking thought and discussion long after the credits roll.